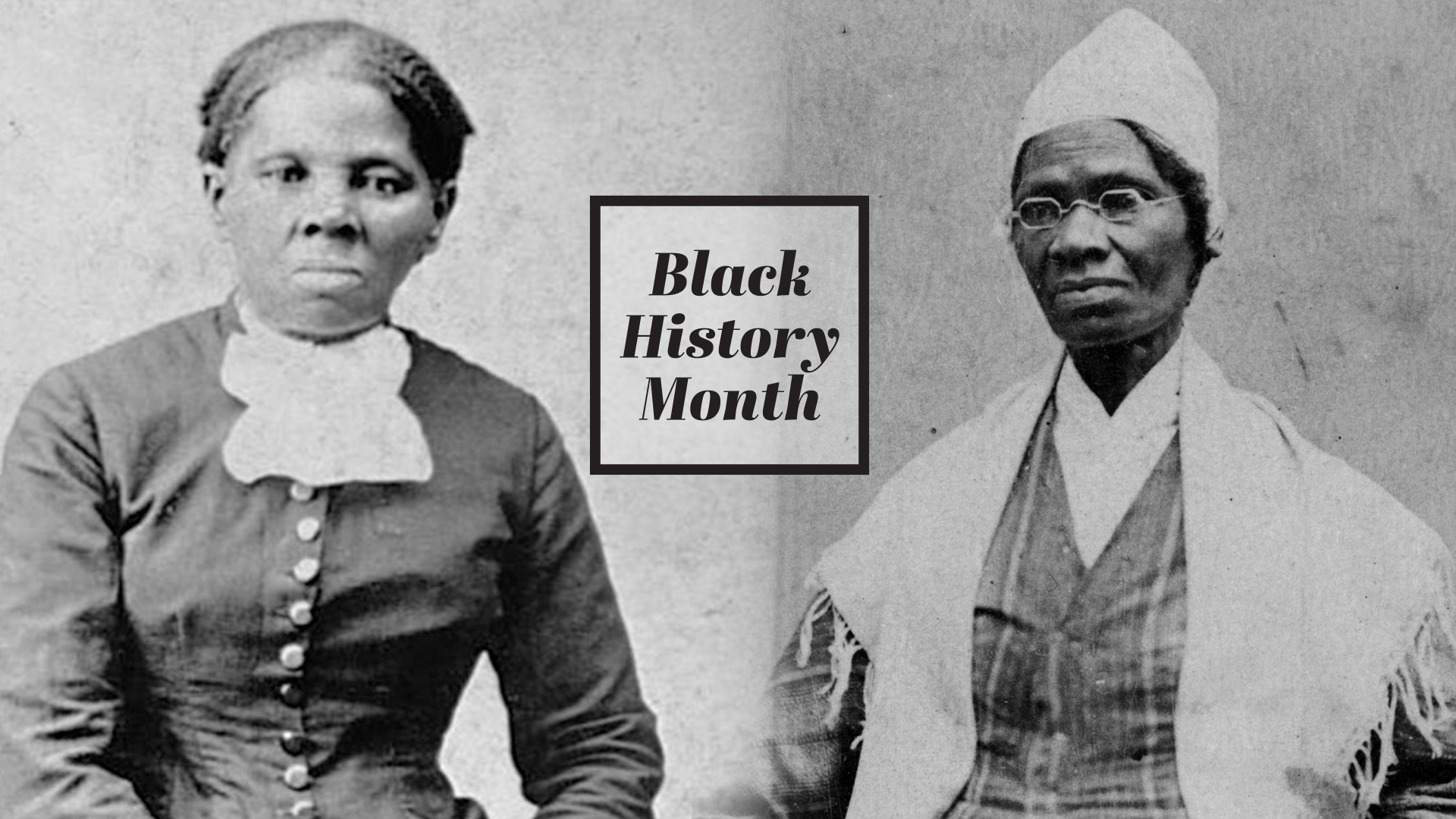

Harriet Tubman (1822-1913) was the most prolific “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, assisting hundreds of slaves to escape bondage and to find freedom in the northern United States and Canada. Her work succeeded due to her reliance upon God and her constant prayer for his guidance. She earned the name “Moses” because she led so many of her fellow African Americans to freedom in the “promised land.”

Harriet was born into slavery to Harriet and Benjamin Ross. Slave owners did not allow slaves’ offspring to be named for their parents to avoid overly strong attachments. So her parents named her Araminta, calling her “Minty.”

A terrible accident during her teen years became a major turning point in Minty’s life. She was in a dry goods store and was caught in the middle of a fight between a runaway slave and his master. The slave owner hurled a two-pound weight at the runaway but instead struck Minty, crushing part of her skull. As a result of her injury, she often suffered splitting headaches, would fall asleep without notice, and most importantly, had dreamlike trances. Later in life, she believed that her trances and visions were God’s revelations to her.

In 1844, Minty married John Tubman, a free black man, and at that time, she took the name “Harriet” to honor her mother. She had a dream that she was to be free, so in 1849, she made her escape. In her flight to freedom, she was aided by Quaker men and women along the Underground Railroad to Philadelphia. Her first feelings of freedom overwhelmed her: “I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person, now that I was free. There was such a glory over everything. The sun came up like gold through the trees and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

Not content with her own freedom, she believed that God told her to help other slaves find their ways to freedom. She made nineteen trips into the South to help deliver at least three hundred fellow slaves to freedom. She boasted, “I never lost a passenger!” And she gave credit to God: “I always told God, I’m going to hold steady to you, and you’ve got to see me through.”

Most often, she conducted her rescues during winter months, when long nights provided cover. And she was clever with disguises to hide her identity. Among those she brought to freedom were her mother and father, but her husband married another woman and remained enslaved.

Once the Civil War broke out, she continued to serve the cause of freedom in the Union Army as a scout and spy. In South Carolina, she helped to lead a military mission up the Combahee River, where she guided Union steamboats around Confederate mines. This successful mission freed 750 slaves, who escaped with the Union army.

After the war, Harriet became involved in the movement for women’s voting rights. When asked if she believed that women ought to have the right to vote, she answered, “I suffered enough to believe it.”

At the turn of the twentieth century, Harriet became involved with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Auburn, New York. She donated a parcel of land to the church to be used as a home for elderly colored people. Eventually, she herself moved into that home and died there in 1913.

In 2019, an Oscar © nominated film was released with her name as the title. Soon her image may appear on the twenty-dollar bill.

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883) was not only an abolitionist but also an itinerant preacher and advocate for women’s suffrage. She stood at six feet tall, commanding the attention of her audiences. During her career, she met with Abraham Lincoln and spoke on platforms with such well-known women as Elizabeth Stanton Cody and Susan B. Anthony.

She was born as Isabella Baumfree in southern New York, when slavery was practiced in the state. During her early years, she was sold several times until she ended up as the property of John Dumont. Dumont’s wife mistreated Isabella verbally, and Dumont raped her, leading to the birth of her daughter Diana. Isabella had four other children by her husband, Thomas.

At dawn one day in 1826, Isabella walked away from slavery, carrying only her infant Sophia. Later she said, “I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right.” She took refuge with a neighboring family who had anti-slavery sympathies.

A couple of years later, Isabella learned that her five-year old son Peter had been sold illegally to a family in Alabama. She took the issue to court and secured Peter’s return. This case was one of the first in which a black woman successfully challenged a white man in a court of law.

About that time, Isabella had a powerful religious experience, when she felt the spiritual presence of Jesus. She had learned about God from the Dutch Calvinists of New York, but she conceived of God as powerful and distant. She said of Jesus, “I saw him as a friend, standing between me and God, through whom love flowed as from a fountain.”

Soon afterward, Isabella moved to New York City with Sophia and Peter. She recognized that the big city was fertile ground for the Gospel. Teaming up with two white women, she evangelized in taverns and brothels. She joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church but spent most of her time working among the city’s outcasts.

In 1843, Isabella felt a call from God: “The Spirit calls me, and I must go!” God gave her a new name, Sojourner Truth, which fit her new direction. She left New York City and began an itinerant preaching ministry. Unable to read or write, Sojourner preached extemporaneously, allowing God to speak through her. Convinced that she was divinely inspired, she was always curious to see what God would say through her.

Speaking to ever-larger, increasingly hospitable audiences, Sojourner preached about repentance and salvation as well as social topics such as abolition, women’s rights, and temperance. Her best known sermon, delivered on behalf of women’s rights, is known by the title “Ain’t I a Woman?” She dictated her autobiography, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave, published by the famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.

During the Civil War, Sojourner, like Harriet, worked for the Union Army, recruiting black troops, and her grandson James Caldwell served in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. She is credited with writing a song, “The Valiant Soldiers,” for the 1st Michigan Colored Regiment. While she worked at the Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, she rode in streetcars to force desegregation in public transportation.

Sojourner Truth died in 1883 in Battle Creek, Michigan. She is remembered by the Episcopal Church in the calendar of saints. A new design for the backside of the ten-dollar bill includes her image alongside other suffragists. And soon a naval ship will bear the name USNS Sojourner Truth.

These African-American Christian women, who faithfully served God and their country, are receiving much deserved attention. They were “valiant soldiers” in the cause of freedom in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Dr. Rex Butler is Professor of Church History and Patristics occupying the John T. Westbrook Chair of Church History.